Stress as a cancer risk factor

In a study published in JAMA Network Open, researchers found that in the 121 Black and White women with breast cancer, perceived stress, perceived inadequate social support, perceived racial and ethnic discrimination, and neighborhood deprivation were associated with suppression of the antitumor immune response, systemic inflammation, and deleterious tumor biologic characteristics. These outcomes were particularly pronounced in Black women.

To read more analysis of the study, see this article published in Medscape.

From the Medscape article:

“But this is fundamentally a study about stress, and so the most important thing that was measured was the women’s level of stress across four domains: daily stress (this is the everyday stuff, such as work, family, and so on), racial discrimination, social isolation, and neighborhood deprivation.

“These four sources of stress were linked to three broad outcomes: immune function writ large, immune function in the area around the tumor, and the biology of the tumor itself.

“There’s a lot here, obviously, so I’ll give you the headline version. Broadly speaking, increased levels of stress screw up the immune system in ways that dramatically improve the environment for cancer cells. But let’s drill down a bit.

“I’ll start with the immune system overall. The response to stress here is a bit complicated. In some ways, stress increases activity in the immune system — which would seem like a good thing. The immune system doesn’t only fight off bacteria and viruses, it also identifies cells that are misbehaving in your body and kills them before they can kill you. But the way stress revs up the immune system is not helpful in preventing cancer. More stress leads to higher levels of things like angiopoietins, which are substances that promote the growth of blood vessels into tissues. Targeting angiopoietins is a mainstay of cancer therapy, because tumors need blood vessels to sustain their growth, so the fact that stress increases their production is very much a bad thing.

“What about the so-called “local immune microenvironment”? This is essentially the cells and tissues right around the cancer — the neighborhood where it is growing. To see what was happening here, researchers looked at the RNA produced by the nearby cells. It’s not good. The authors found that while some immune cells, such as M1 macrophages, are ramped up, so are M2 macrophages, which actually suppress immune function. Most concerningly, cells that are particularly good at eradicating tumor cells — known as natural killer cells and follicular helper T-cells — are downregulated. If the immune system is the police force in your body, stress seems to fire the best detectives and replace them with desk jockeys who would rather eat donuts than pound leather.

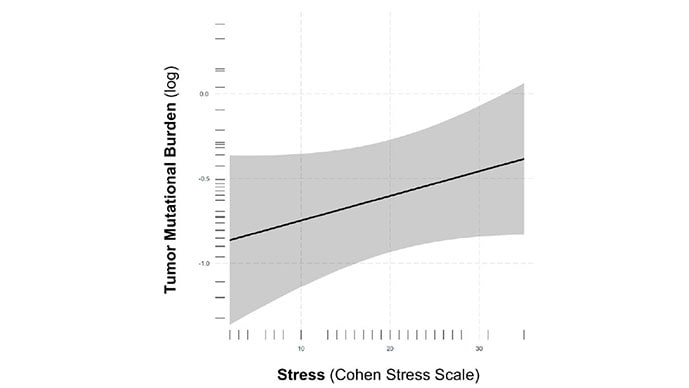

“It might not all be bad. Higher levels of stress led to an increase in tumor mutational burden — more genetic errors in the tumor itself. This is a bit of a double-edged sword. Higher mutational burden can mean a more aggressive cancer, but at the same time the cancers may be more susceptible to immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy — blockbuster anti-cancer drugs.

“It’s worth noting that these effects were generally more pronounced in Black compared with white women, which may provide some explanation on why breast cancer incidence and severity are higher in that population.

“I should also note that although racial discrimination, social isolation, and neighborhood deprivation all had significant relationships with some pro-cancer markers, simple prolonged daily stress had the most consistent relationship across all the domains. Which makes sense, honestly. After all, things like racial discrimination, social isolation, and neighborhood deprivation increase stress levels — that’s probably part of the reason they have such adverse outcomes on health.

“A study with this many comparisons between exposures and outcomes is necessarily going to be complex to process, and I see it more as an initial shotgun approach to understanding the convoluted interplay between psychology and biology that influences cancer growth than a definitive treatment of the subject. Future studies will no doubt drill down further on these issues, perhaps revealing new anti-tumor targets.

“In the meantime, what do we do? Well, it may be time to add stress to our list of cancer risk factors. And for people with cancer, sure, it’s easy to say “don’t stress.” It’s harder to practice it. There are studies that have evaluated yoga and mindfulness meditation in cancer, with some encouraging results. Of course, that won’t be right for everyone. Finding out what reduces that “perceived daily stress” in your own life — whether it’s yoga or golf or spending time with loved ones or playing video games — is a worthwhile endeavor. Your body, and your local immune microenvironment, will thank you.”

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. His science communication work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and here on Medscape. He posts at @fperrywilsonand his book, How Medicine Works and When It Doesn’t, is available now.